We recently caught up with Ravin Jesuthasan, Managing Director at Willis Towers Watson, as he prepared for the launch of his most recent book, Reinventing Jobs: A 4-Step Approach for Applying Automation to Work (with John Boudreau). Reinventing Jobs is available on Amazon Kindle now, and will be available in print on October 9th.

Ravin will host the TWIN challenge session on Automation and the Future of Work this coming Tuesday, September 25th at 9 AM. He will also be part of our Wednesday panel, which is also titled Automation and the Future of Work.

The pre-session is sponsored by Willis Towers Watson.

The pre-session is sponsored by Willis Towers Watson.

Bryan Campen: So maybe we can just jump in to what you believe is the biggest issue workers and leaders are facing now…

Ravin Jesuthasan: The big pivot for us as human beings is this new requirement, to reinvent ourselves as automation increasingly substitutes for the routine, independently performed aspects of our work and augments yet other elements. This notion of perpetually upgrading oneself in much the same as we expect from our personal technology. Anyone who does not reinvent themselves risks being left behind much faster than ever before.

From a leadership perspective, the major shift is the recognition is that no longer can we think of our organizations as self-contained. Every organization is either the hub or spoke of a broader ecosystem for work. We need to create permeable organizations where talent and work can flow more seamlessly. This is going to be really essential for every leader.

I’ll give you a specific example, one we are seeing with a lot of our clients and the book illustrates this a fair bit: You’ve got this new ecosystem for work.

Traditionally your choices were to hire or acquire talent, develop the talent organically, or outsource the work. Today you have up to eight different means. These range from tapping into talent from platforms such as Upwork, engaging with a robotic process automation vendor, or using Microsoft Azure to develop your own AI, to take on various types of work.

Ravin Jesuthasan: The big pivot for us as human beings is this new requirement, to reinvent ourselves as automation increasingly substitutes for the routine, independently performed aspects of our work and augments yet other elements. This notion of perpetually upgrading oneself in much the same as we expect from our personal technology. Anyone who does not reinvent themselves risks being left behind much faster than ever before.

From a leadership perspective, the major shift is the recognition is that no longer can we think of our organizations as self-contained. Every organization is either the hub or spoke of a broader ecosystem for work. We need to create permeable organizations where talent and work can flow more seamlessly. This is going to be really essential for every leader.

I’ll give you a specific example, one we are seeing with a lot of our clients and the book illustrates this a fair bit: You’ve got this new ecosystem for work.

Traditionally your choices were to hire or acquire talent, develop the talent organically, or outsource the work. Today you have up to eight different means. These range from tapping into talent from platforms such as Upwork, engaging with a robotic process automation vendor, or using Microsoft Azure to develop your own AI, to take on various types of work.

The leader of the future is that person who figures out how she is going to orchestrate this new ecosystem for work, and when it makes sense to use one particular option versus potentially tapping into another, or when it makes sense to move from one option to another. In all of this, one key skill is to continuously challenge yourself, to ask yourself the question “am I stuck doing highly repetitive, rules-based work that an algorithm could be trained to do quite easily?” Knowing where substitution of human labor versus augmentation of human skills versus the creation of new human work as a result of automation will be vital.

BC: What’s an example of a new type of work that you see is increasing in demand?

RJ: The most obvious is the rapid growth in demand we’ve seen for highly sophisticated and capable data scientists. In part this is because we have so much data coming off sensors, and because of the power we have to process that data with machine learning. This is work that wouldn’t exist if we didn’t have these advances in sensors and AI.

RJ: The most obvious is the rapid growth in demand we’ve seen for highly sophisticated and capable data scientists. In part this is because we have so much data coming off sensors, and because of the power we have to process that data with machine learning. This is work that wouldn’t exist if we didn’t have these advances in sensors and AI.

BC: Where is AI operating alongside humans, and could you tell us a bit more about that?

RJ: We have seen the use of AI in call center operations, not to substitute the human being but to augment their capabilities. One example in the book is of natural language processing algorithms that can recognize emotions in voices and within seconds direct a highly emotive caller to the company’s best call center representatives, while providing that representative with the optimal script for dealing with that person or dealing with his or her unique challenges.

RJ: We have seen the use of AI in call center operations, not to substitute the human being but to augment their capabilities. One example in the book is of natural language processing algorithms that can recognize emotions in voices and within seconds direct a highly emotive caller to the company’s best call center representatives, while providing that representative with the optimal script for dealing with that person or dealing with his or her unique challenges.

BC: So it complements rather than replaces.

RJ: Yes, and we must continually ask ourselves the question of where we as humans or employees have a comparative advantage over an alternative source of work—that’s not a new question, right? We’ve been asking ourselves that question since the second industrial revolution. We asked ourselves that question a lot as a society as we went through the third industrial revolution, where we started to see more and more outsourcing. In that instance the question was less of one for humanity and more of one of, “How am I adding value versus my equally-skilled but lesser-cost peers in another part of the world”?

RJ: Yes, and we must continually ask ourselves the question of where we as humans or employees have a comparative advantage over an alternative source of work—that’s not a new question, right? We’ve been asking ourselves that question since the second industrial revolution. We asked ourselves that question a lot as a society as we went through the third industrial revolution, where we started to see more and more outsourcing. In that instance the question was less of one for humanity and more of one of, “How am I adding value versus my equally-skilled but lesser-cost peers in another part of the world”?

BC: So much of this comes down to your point on reskilling. What do you think leaders should be focused on in terms of helping their teams reskill?

RJ:The reskilling imperative is going to be the most significant imperative in this fourth industrial revolution. One project we are currently at work on with the World Economic Forum relates to creating a shared vision for talent in the fourth industrial revolution. What will be critical is for leaders to empower and equip their talent to be able to continuously take a framework like the one we present in Reinventing Jobs to, deconstruct their jobs, identify how automation can make a difference, and motivate them to want to keep reinventing their work. At the same time leaders need to give workers the opportunity to identify where their existing skills can be deployed for higher gain, and discover what new skills they need to develop in order to remain relevant.

RJ:The reskilling imperative is going to be the most significant imperative in this fourth industrial revolution. One project we are currently at work on with the World Economic Forum relates to creating a shared vision for talent in the fourth industrial revolution. What will be critical is for leaders to empower and equip their talent to be able to continuously take a framework like the one we present in Reinventing Jobs to, deconstruct their jobs, identify how automation can make a difference, and motivate them to want to keep reinventing their work. At the same time leaders need to give workers the opportunity to identify where their existing skills can be deployed for higher gain, and discover what new skills they need to develop in order to remain relevant.

BC: Can you give us a brief overview of the framework in Reinventing Jobs?

RJ: Sure. It is a four-step process developed to help business leaders identify the optimal combinations between humans and machines.

The first step is about really understanding the work. It’s about deconstructing the job into its tasks, and categorizing those tasks along three continuums: First, understanding what is highly repetitive versus what is variable, then what is mental in nature versus physical, and finally what is performed independently versus interactively.

Once you deconstruct you then ask what you are trying to solve for: what’s the relationship between the performance of that particular task and the value of that performance to the organization? Is it to minimize errors, to reduce the variance of performance? Is it to improve productivity, or is it in fact to create a fundamentally new and different experience?

RJ: Sure. It is a four-step process developed to help business leaders identify the optimal combinations between humans and machines.

The first step is about really understanding the work. It’s about deconstructing the job into its tasks, and categorizing those tasks along three continuums: First, understanding what is highly repetitive versus what is variable, then what is mental in nature versus physical, and finally what is performed independently versus interactively.

Once you deconstruct you then ask what you are trying to solve for: what’s the relationship between the performance of that particular task and the value of that performance to the organization? Is it to minimize errors, to reduce the variance of performance? Is it to improve productivity, or is it in fact to create a fundamentally new and different experience?

When the work is understood, you then have the opportunity to understand the specific type of automation that is relevant for that work, whether it’s robotic process automation, or cognitive automation—i.e. artificial intelligence, or social robotics.

After the work is understood, you then can identify the role of that automation. Is it to substitute? Is it to augment? Or is it to transform the work and in some cases actually create new types of work for humans that machines can’t do?

After the work is understood, you then can identify the role of that automation. Is it to substitute? Is it to augment? Or is it to transform the work and in some cases actually create new types of work for humans that machines can’t do?

BC: It seems so vital, and at the same time it appears that this conversation really has not penetrated political spheres at a very high level in the United States. What do you think the biggest risk is regarding policy-making in the US, and the reinvention of jobs, and what are some useful examples at a global level?

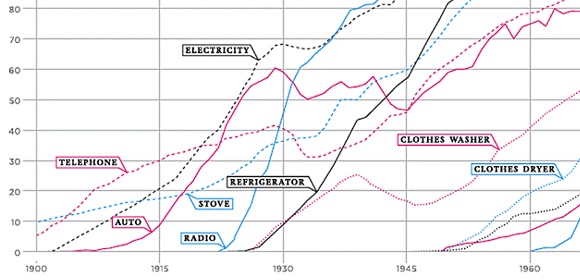

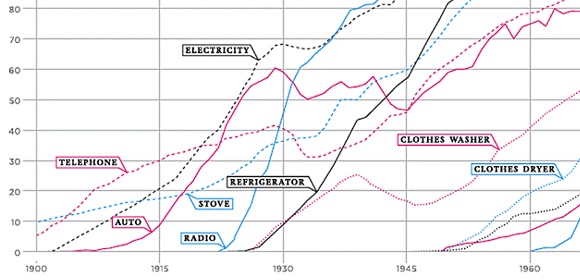

Above: A chart showing the increasing speed of technological adoption over the past century

Above: A chart showing the increasing speed of technological adoption over the past century

Source: Visual Economics, via The Atlantic Monthly

RJ: It is a big risk, and I see this in a variety of spheres, not just government. But thinking that things will be ok in the end, and that the traditional tools we have will suffice in getting us through this is incorrect. We are seeing that the speed with which the world is changing is far greater than anything we’ve seen to date, coupled with the rates of adoption. The speed of adoption today is not just two or three times faster than, for example, the speed with which the lightbulb or the fridge was adopted, its 40, 50 or 100 times faster. There is a real risk of redundancy from a policy perspective, because policymakers tend to be so much slower in responding and often think that the quantum of their response can be the same as in the past. Well it can’t be this time around.

BC: What needs to happen, in your mind, to adapt policy and this wave of change to one another?

RJ: Most importantly, what we need is a much more collaborative approach to change than we in this country are traditionally used to. It can’t just be about government-driven policy, or leaving companies to it. Nor can we leave the educational sector to do it. It’s going to really require a three-part response that involves all three entities—government, business and education— working together.

RJ: Most importantly, what we need is a much more collaborative approach to change than we in this country are traditionally used to. It can’t just be about government-driven policy, or leaving companies to it. Nor can we leave the educational sector to do it. It’s going to really require a three-part response that involves all three entities—government, business and education— working together.

BC: In terms of policy and approach, what is a standout example of a government addressing the influx of automation and robotics?

RJ: We as a firm are very involved with the Singapore government’s Skills Future initiative. And I have been very impressed with how the government has started to play a role in helping industry think through how skills are evolving across different sectors, involving the educational sector in helping industry meet some of those changing needs, and at the same time putting in place incentives for individual citizens to get reskilled. Granted, Singapore is a very small economy and it hasn’t got the challenges of scale as the US or other western democracies, but the way they have approached it can be pretty useful to any economy.

RJ: We as a firm are very involved with the Singapore government’s Skills Future initiative. And I have been very impressed with how the government has started to play a role in helping industry think through how skills are evolving across different sectors, involving the educational sector in helping industry meet some of those changing needs, and at the same time putting in place incentives for individual citizens to get reskilled. Granted, Singapore is a very small economy and it hasn’t got the challenges of scale as the US or other western democracies, but the way they have approached it can be pretty useful to any economy.

BC: What’s impressed you the most about their approach overall?

RJ: I think the fact they have viewed this as less of an approach of saying “We are going to impose new regulations or determine new skills on our own as a government”, but instead they have said, “We are going to involve all of the companies that make up each of these industries and involve the education sector. We’re going to take on a much more collaborative approach, and think about how work is evolving, how automation will shift skill premiums, to start to identify the types of skills that are going to be most critical” both within and across something like 20 different industries.

RJ: I think the fact they have viewed this as less of an approach of saying “We are going to impose new regulations or determine new skills on our own as a government”, but instead they have said, “We are going to involve all of the companies that make up each of these industries and involve the education sector. We’re going to take on a much more collaborative approach, and think about how work is evolving, how automation will shift skill premiums, to start to identify the types of skills that are going to be most critical” both within and across something like 20 different industries.

BC: Do you see universal basic income (UBI) anywhere in the mix in terms of addressing the reinvention of jobs?

RJ: This is not a new idea, it’s one that has been around for a long time. But the quantum of disruption we are facing today perhaps makes it worthwhile to study again, to see if in fact universal basic income could be part of the overall response to the disruption we might be facing as a result of automation. I am aware of the UBI experiments in Western Europe, India and Africa, or here in the US, in Stockton. It is going to be fascinating to see what the outcome of these experiments are.

RJ: This is not a new idea, it’s one that has been around for a long time. But the quantum of disruption we are facing today perhaps makes it worthwhile to study again, to see if in fact universal basic income could be part of the overall response to the disruption we might be facing as a result of automation. I am aware of the UBI experiments in Western Europe, India and Africa, or here in the US, in Stockton. It is going to be fascinating to see what the outcome of these experiments are.

BC: Last question: Out of all of the potential jobs, what do you see as a job in the future, say five years out, that does not exist yet?

RJ: I will go back to my point about one of the key skills for a leader, and that skill is going to be his or her ability to orchestrate this new ecosystem for work. I do think there is going to be demand for—for want of a better phrase— a “work orchestrator”. That individual is someone who sits in a strategy/HR position and is continually evaluating different options for the organization to get different pieces of work done, and continuously asking what are the speed, productivity, cost, risk and capital implications associated with each option.

RJ: I will go back to my point about one of the key skills for a leader, and that skill is going to be his or her ability to orchestrate this new ecosystem for work. I do think there is going to be demand for—for want of a better phrase— a “work orchestrator”. That individual is someone who sits in a strategy/HR position and is continually evaluating different options for the organization to get different pieces of work done, and continuously asking what are the speed, productivity, cost, risk and capital implications associated with each option.

There is growing demand for a role that is responsible for helping the organization continually assess how its work gets done, tapping into the eight different means.

Reinventing Jobs is out now on Kindle. It will be available in hardcover on October 9th.

Reinventing Jobs is out now on Kindle. It will be available in hardcover on October 9th.