The Trump 2020 Death Star

Parscale chose an awkward metaphor. Perhaps he’s attracted by the Death Star’s mission to destroy all dissent across the Empire— emblematic of today’s looming threats to democracy.

Returning To Earth

Balasubramaniyan posited, “disinformation and its designers have more tools and more willing participants at their disposal than ever before.” To illustrate the magnitude of the challenge, as of the date of our panel, Pindrop had raised over $250 million. They’re a leader in combating deep fakes— just one manifestation of media exploitation for nefarious ends.

The Future of Truth discussion at TWIN Global 2019, September 17 at the Harris Theater, Chicago. Panelists (from left) Kristian Hammond, Vijay Balasubramaniyan and Marjorie Paillon discuss deep fakes, social media, journalism and our search for truth with moderator and TWIN Global Co-Founder & Chairman, Rob Wolcott. TWIN GLOBAL/OEMIG

While many of us would like to believe that ‘one truth’ exists, millennia of history should disavow us of such a comfortable notion. As a journalist, Paillon observed, “There is no such thing as neutrality…. It’s my duty to give you as much subjectivity as possible,” for you to build your own perspectives.

While navigating social media, Hammond cautioned that, “it’s the things you want the most that are… usually not the things that are true— because you want them so badly.” Any time a story or soundbite feels so right, be the most skeptical. Someone could be pulling your levers.

During the Covid-19 crisis, rational debates regarding reopening have been complicated by ever more fantastical (read: ‘idiotic’) conspiracy theories. If you believe—or wonder— if Bill Gates created COVID to inject each of us with tracking chips, you’ve been duped. There are so many realities wrong with that position. Social media makes it likely more such dangerous fairy tales will percolate.

The Propaganda Machine Evolves

As John Meacham pointed out in Thomas Jefferson: President and Philosopher, numerous early American politicians donned pseudonyms and spread blatant lies through intensely partisan broadsheets. Jefferson’s campaign became known as one of the dirtiest in American history.

During the 20th century mass media era, often intertwined government and business interests commanded access to publications and broadcast networks. Widespread dissemination of information and agenda-laden misinformation was almost exclusively controlled by the few.

While social media platforms democratize access, they do not democratize influence. Anyone can participate, create and share. Online movements sometimes do arise from collective groundswell.

The US Presidential Election of 1800 was such a dramatic and dirty affair that it featured in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s historical musical “Hamilton.” Here, Miranda and cast perform at the Tony Awards in New York in 2016.

Echoing Marshall McLuhan, the medium truly has become the message. Social media appears to shape public dialogues in a non-directed, emergent manner from the convergent, colliding perspectives of individuals. Often it does so. Sometimes it provides fogs and screens for powerful interests.

In a commencement speech in 2005, American novelist David Foster Wallace opened with a joke. “There are two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys, how’s the water?” The two young fish swim on and eventually ask one another, “What the hell is water?” It was Plato’s Cave rewritten for our social media age.

Death Star 1.0

One of the most powerful pieces of filmmaking, Triumph of the Will, was also one of the most vile. Hitler’s filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl deployed groundbreaking shots and editing techniques.

While abhorring the spirit and objectives of the film, many of the 20th century’s top filmmakers ranked the film as a work of art. I encourage you to see the film— though keep clearly in mind the repugnance of purpose and devastation that ensued.

Consider the case of William Shirer, CBS correspondent to Berlin during World War Two. Shirer was the American closest to the largest propaganda operation in history (to date) as it went to war with the US. Near Joseph Goebbels’s Berlin headquarters, he received daily copies of newspapers from London, Paris and Zurich, and daily BBC broadcasts—illegal for most German citizens.

Leni Riefenstahl (center) directing a particularly difficult shot during the Nuremburg Rallies, footage which became part of the film “Triumph of the Will.” BUNDESARCHIV/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Shirer’s observations reflect the consternation many of us feel today as we observe the behaviors of otherwise smart, competent, often well-meaning people— even possibly ourselves— “parroting some piece of nonsense they had heard on the radio or read in the newspapers.”

Confronting Goebbels’s lies, Shirer sometimes struggled with discerning the truth. What chance do the rest of us have?

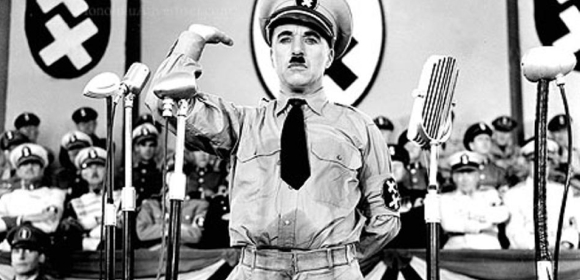

As an antidote to the destructive mania of the age, Charlie Chaplin— the first Hollywood millionaire— produced and starred in the meaningful parody The Great Dictator. I’d recommend watching that as soon as you finish Reifenstahl’s film.

Charlie Chaplin as the dictator, Adenoid Hynkel, in the 1940 satire, The Great Dictator. WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, AP

Death Stars Within

Humans believing, even against rationality, is not new. The nature of the medium is: social media’s distributed, targeted, profligate reproduction and mutation. Text on paper changes slowly. Broadcast television reaches millions with linear messages. Social media assails from all directions, infects and ricochets.

Paraphrasing journalist Marjorie Paillon, we must find and synthesize sources, gather multiple truths and consider our own subjectivities. Given the scale and complexity of the task, we “must rely on a combination of technology and humans,” as Pindrop’s Balasubramaniyan advised.

Pindrop CEO & Founder, Vijay Balasubrimaniyan explores how technology can help us combat deep fakes and find actionable versions of truth. TWIN GLOBAL/OEMIG